MontyB

All-Blacks Supporter

Even though we celebrate it on the 9th of May (8th May Euro-time) here I prefer to regard the 7th as the proper date even if the Russians disagree.

VE Day

Germany surrendered in the early afternoon of 7 May 1945, New Zealand time. The news became known the next morning, with huge headlines in the morning papers. But the acting prime minister, Walter Nash, insisted that celebrations should wait until British Prime Minister Winston Churchill officially announced the peace, which would not be heard in New Zealand until 1 a.m. on 9 May. So on Tuesday, 8 May, when everybody felt like celebrating, Nash told the country by radio that they should all go to work and that VE Day would be on the 9th.

Celebration by instruction

The feeling of victory was in the air, but no-one was inclined to let off steam without official authorisation ... The mayor of a local body hit the nail on the head when he remarked, 'In 20 years' time, school children will be asked to define the word anti-climax, and the answer will be "March [sic] 8, 1945".'

New Zealand Herald, 9 May 1945

Most New Zealanders accepted the edict. They were not 'inclined to let off steam without official authorisation'. Only Dunedin bucked the trend. There, the holding of the university's capping parade released the inhibitions. By midday the factory workers had downed tools. The town hall bells were rung, and the mayor held a short ceremony in the Octagon. Even then, this spontaneous celebration never exceeded the bounds of decorum.

On VE Day itself weeks of official preparation rolled into action. Citizens were woken by bells and sirens, and flags quickly appeared. At the Government Buildings in Wellington there were speeches by the governor-general, the acting prime minister and the leader of the opposition. The American, Soviet and New Zealand national anthems were sung, and only then, after midday, did official local ceremonies start.

These local programmes of events, which generally extended over the next day, 10 May, which was also a public holiday, were highly orchestrated affairs. There were bands parading, community sing-songs, thanksgiving services (often held at the local war memorial), and, in smaller places, bonfires and sports programmes for the children and victory balls for the adults. In Wellington music was played at three sites, and there was a victory service at the Basin Reserve. In Christchurch the Trades Council organised a People's Victory March in which 25,000 paraded from Latimer Square to Cathedral Square singing patriotic ditties.

The organised ceremonies were in part designed to keep the lid on more spontaneous celebration. There was, of course, plenty of spontaneity – the pubs were full, and in Wellington there was broken glass in the streets, and government documents and confetti were thrown out of windows. There was singing and dancing in the streets and strangers kissing. People joined together in crocodile lines and took part in impromptu street theatre. But it never got out of hand. There was little damage to property, and in both Wellington and Auckland, there was just one case brought before the courts the next day. Elsewhere, citizens were complimented on their 'commendable restraint'.

------------------------------------

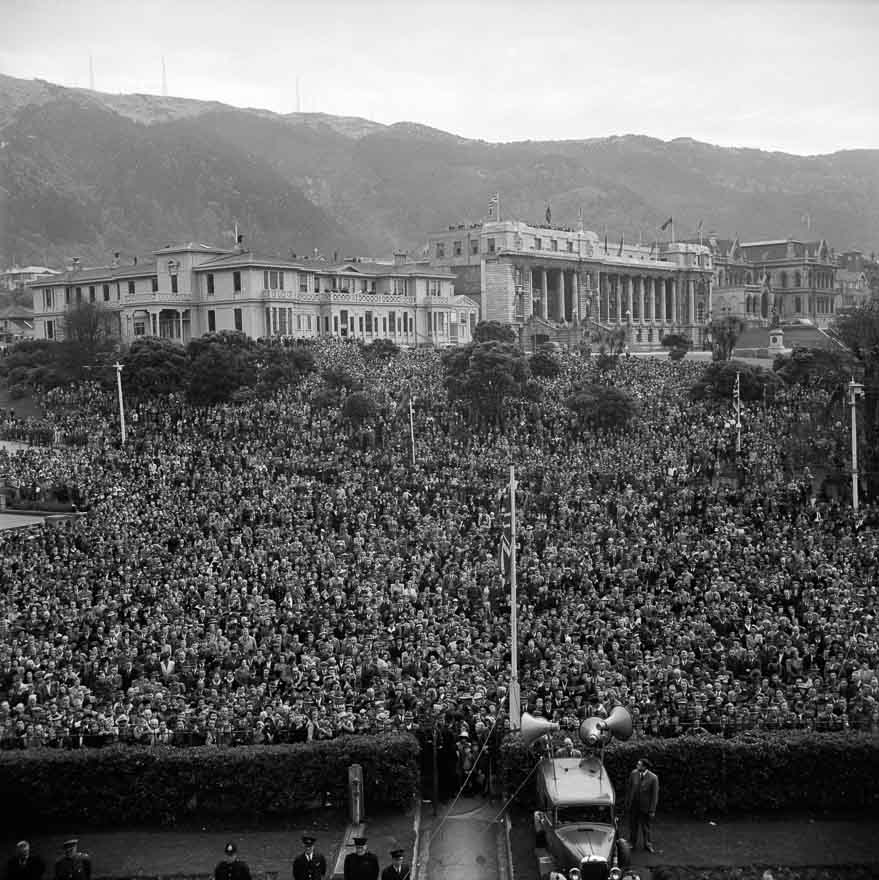

VE Day celebrations at the New Zealand Parliament

Crowds gather in front of Parliament Buildings in Wellington to celebrate victory in Europe.

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/ve-day

New Zealand and the Second World War

Our part in a global conflict

The Second World War was the greatest conflict ever to engulf the world. It took the lives of 50 million people, including one in every 150 New Zealanders, and shaped the world that we have lived in ever since.

New Zealand was involved for all but three of the 2179 days of the war — a commitment on a par only with Britain and Australia. It was a war in which New Zealanders gave their greatest national effort — on land, on the sea and in the air — and a war that New Zealanders fought globally, from Egypt, Italy and Greece to Japan and the Pacific.

The impact on the home front was considerable. The nature of the Second World War not only gave impetus to New Zealanders' developing sense of identity but also greatly increased their confidence in their role in the world.

Quick facts and figures:

- The population of New Zealand in 1940 was about 1,600,000.

- About 140,000 New Zealand men and women served, 104,000 in 2NZEF, the rest in the British or New Zealand naval or air forces.

- Fatal casualties during the conflict numbered 11,928 (Commonwealth War Graves Commission figures).

- Post-war calculations indicated that New Zealand's ratio of killed per million of population (at 6684) was the highest in the Commonwealth (with Britain at 5123 and Australia, 3232).

- In contrast to its entry into the First World War, New Zealand acted in its own right by formally declaring war on Germany on 3 September (unlike Australia, which held that the King's declaration, as in 1914, automatically extended to all his Dominions).

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/new-zealand-and-the-second-world-war-overview

VE Day

Germany surrendered in the early afternoon of 7 May 1945, New Zealand time. The news became known the next morning, with huge headlines in the morning papers. But the acting prime minister, Walter Nash, insisted that celebrations should wait until British Prime Minister Winston Churchill officially announced the peace, which would not be heard in New Zealand until 1 a.m. on 9 May. So on Tuesday, 8 May, when everybody felt like celebrating, Nash told the country by radio that they should all go to work and that VE Day would be on the 9th.

Celebration by instruction

The feeling of victory was in the air, but no-one was inclined to let off steam without official authorisation ... The mayor of a local body hit the nail on the head when he remarked, 'In 20 years' time, school children will be asked to define the word anti-climax, and the answer will be "March [sic] 8, 1945".'

New Zealand Herald, 9 May 1945

Most New Zealanders accepted the edict. They were not 'inclined to let off steam without official authorisation'. Only Dunedin bucked the trend. There, the holding of the university's capping parade released the inhibitions. By midday the factory workers had downed tools. The town hall bells were rung, and the mayor held a short ceremony in the Octagon. Even then, this spontaneous celebration never exceeded the bounds of decorum.

On VE Day itself weeks of official preparation rolled into action. Citizens were woken by bells and sirens, and flags quickly appeared. At the Government Buildings in Wellington there were speeches by the governor-general, the acting prime minister and the leader of the opposition. The American, Soviet and New Zealand national anthems were sung, and only then, after midday, did official local ceremonies start.

These local programmes of events, which generally extended over the next day, 10 May, which was also a public holiday, were highly orchestrated affairs. There were bands parading, community sing-songs, thanksgiving services (often held at the local war memorial), and, in smaller places, bonfires and sports programmes for the children and victory balls for the adults. In Wellington music was played at three sites, and there was a victory service at the Basin Reserve. In Christchurch the Trades Council organised a People's Victory March in which 25,000 paraded from Latimer Square to Cathedral Square singing patriotic ditties.

The organised ceremonies were in part designed to keep the lid on more spontaneous celebration. There was, of course, plenty of spontaneity – the pubs were full, and in Wellington there was broken glass in the streets, and government documents and confetti were thrown out of windows. There was singing and dancing in the streets and strangers kissing. People joined together in crocodile lines and took part in impromptu street theatre. But it never got out of hand. There was little damage to property, and in both Wellington and Auckland, there was just one case brought before the courts the next day. Elsewhere, citizens were complimented on their 'commendable restraint'.

------------------------------------

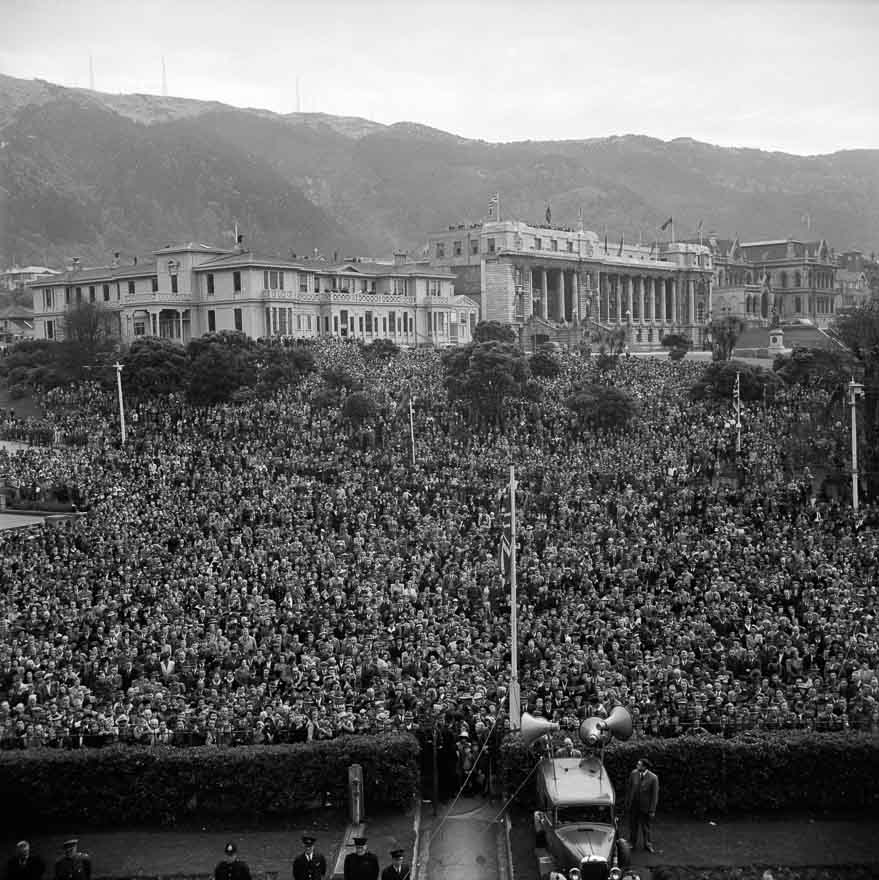

VE Day celebrations at the New Zealand Parliament

Crowds gather in front of Parliament Buildings in Wellington to celebrate victory in Europe.

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/ve-day

New Zealand and the Second World War

Our part in a global conflict

The Second World War was the greatest conflict ever to engulf the world. It took the lives of 50 million people, including one in every 150 New Zealanders, and shaped the world that we have lived in ever since.

New Zealand was involved for all but three of the 2179 days of the war — a commitment on a par only with Britain and Australia. It was a war in which New Zealanders gave their greatest national effort — on land, on the sea and in the air — and a war that New Zealanders fought globally, from Egypt, Italy and Greece to Japan and the Pacific.

The impact on the home front was considerable. The nature of the Second World War not only gave impetus to New Zealanders' developing sense of identity but also greatly increased their confidence in their role in the world.

Quick facts and figures:

- The population of New Zealand in 1940 was about 1,600,000.

- About 140,000 New Zealand men and women served, 104,000 in 2NZEF, the rest in the British or New Zealand naval or air forces.

- Fatal casualties during the conflict numbered 11,928 (Commonwealth War Graves Commission figures).

- Post-war calculations indicated that New Zealand's ratio of killed per million of population (at 6684) was the highest in the Commonwealth (with Britain at 5123 and Australia, 3232).

- In contrast to its entry into the First World War, New Zealand acted in its own right by formally declaring war on Germany on 3 September (unlike Australia, which held that the King's declaration, as in 1914, automatically extended to all his Dominions).

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/new-zealand-and-the-second-world-war-overview