Hi,

Forty years have elapsed since the 1962 war, but its shadow still influences Sino-India relations.

China and India, having a long history of friendly interaction and a fine tradition of learning from each other, both suffered from imperialist and colonialist aggression, oppression and exploitation.

After achieving their independence and liberation, respectively, in the late 1940s, they should have treated each other on an equal footing, supported each other, and learnt from each other in the reconstruction of their own countries, to enable the peoples of both countries to lead a happy life. But it was deplorable that due to the misperceptions and mistaken policies of a few leaders, the development of Sino-India relations took a winding path.

As for the genesis of the 1962 war, since many eminent scholars across the world, such as Neville Maxwell, Karunakar Gupta, and Steven Hoffmann, have made in-depth studies, it is not pertinent for me to dwell on it here. But it should be noted that the Nehru government not only took over the legacy of British imperialist strategic perceptions of security and interfered many times with the Tibet affairs of China, it also demonstrated more arrogance and irrationality on boundary issues than the Raj.

The British imperialists did draw an illegal McMahon Line, but they dared not occupy in reality the territories of China to the south of that line. But the Nehru government did just that.

Evidence indicates that in the early years after independence, Jawaharlal Nehru himself privately instructed B N Mullick, head of the Intelligence Bureau, to count China as an enemy. It was under his approval that armed Indian border guards drove away the Tibetan administrators and occupied Sela by force in 1948, and Tawang and other Chinese territories to the south of the McMahon Line in 1952. But Nehru's government did not stop here; it sought to decide for itself where India's borders with China should lie and then impose the alignments it had chosen on China.

In 1960, the Nehru government not only refused publicly to negotiate with Premier Zhou Enlai who made a special trip to New Delhi to seek a friendly settlement of boundary issue, but rejected any standstill agreement.

In the following year, it ordered the 'Forward Policy', under which the Indian Army relentlessly attacked the People's Liberation Army's posts along the entire border and killed many Chinese soldiers in an attempt to extrude them out of all the Chinese territory it claimed.

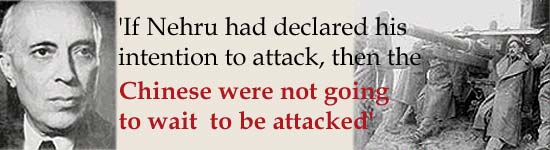

This aggressive and provocative policy not only interrupted the status quo, but also breached the peace and tranquillity along the entire border. In October 1962, Nehru ordered the army to take the offensive and made a statement about it on the 12th of the same month. His statement shocked the whole world. The New York Herald Tribune published an editorial entitled 'Nehru Declares A War Against China' the following day.

All honest and sober-minded people could see that the 1962 war was imposed on China by the Nehru government. China had no other way out but to launch a counter-attack and take preventive action. The purposes were:

1. To defend peace and tranquillity along the entire border;

2. To bring the Nehru government back to the negotiating table.

China had no intention to solve the boundary issue by force, which was proved by the fact that as soon as the PLA won the war, it returned to its original posts.

But how did the Nehru government explain the event to the Indian public? It had no courage to admit its mistakes and tell the truth, but adopted dishonest and irrational means to blame it on China, saying China conducted an "unprovoked aggression" against India, and China "betrayed India".

This frame-up produced two kinds of negative and malignant consequences: first, China was turned into a devil in the mind of the Indian public; second, it led to a long-term confrontation between the two countries and caused a huge waste of manpower and material resources on both sides. These negative and malignant consequences really made those who were keen to maintain Sino-Indian friendship distressed.

Though such was the case, we have no reason to be crestfallen. As the saying goes, misfortune might be a blessing in disguise. If the successors can learn the real lessons from the mistakes of their predecessors and turn them into lasting action, it will allow the people of both nations to own an invaluable precious wealth.

Thanks to the late Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi's historic visit to China in 1988, Sino-India relations have gradually regained normalcy. During Indian prime minister P V Narasimha Rao's visit to China in 1993, both sides signed the Agreement on Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity along the Line of Actual Control in the China-India Border Areas.

In 1996, a further agreement on "confidence-building measures in the military field along the LAC" was signed during President Jiang Zemin's visit to India. All these demonstrated that the two governments had become far-sighted and mature. This is the very reason why Sino-India relations developed smoothly and quickly on the whole during the last more than 10 years, though it took an unexpected turn in 1998.

But we should not sit back. It should be noted that, in terms of populations, sizes, economic scales, and the roles played in the contemporary world by China and India, the co-operation between them is far from what it should be.

What has obstructed Sino-India relations from developing in depth and giving full play to the potential of both?

There are both objective and subjective factors. Judging from the present conditions, it seems that the subjective factors are prevailing, and the resistance is mainly from the Indian side.

Why am I saying so? Because on the Indian side there still are a considerable number of officials, soldiers and think tanks who have not walked out of the shadow of the 1962 war. Many of them adhere, consciously or unconsciously, to the strategic perception of security prevailing in old times, and count China as a threat or a potential adversary. Given such a psychology, how can they expect to further develop Sino-India relations?

But I don't complain about them, because the majority of them were also misled in the past. I believe that, with increasing mutual exchanges, the day will come when they will realise that China is a true friend and brother of India. Now the challenge facing us is, how effectively will far-sighted statesmen and those of insight make public the truth of the 1962 war?

Let that day come earlier. On the day when Sino-India misunderstanding is thoroughly dispersed, an era for in-depth Sino-India co-operation will come.

By : Wang Hongwei is professor of South Asia regional studies at the Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and adviser to the Chinese Association for South Asian Studies. He is the author of several books, including The Himalayas Sentiment: A Study of Sino-Indian Relations (1998 ) and The Present Situation and Future of The South Asia Regional Cooperation (1993), and more than 100 papers, commentaries, treatises and prose relating to South Asia and Sino-Indian relations.

totally neutral source? :type:

Peace

-=SF_13=-